At a party several months ago, I overheard, and was drawn into, an interesting conversation while en route to the bathroom.

The conversation was about finances, naturally. A friend of mine was admonishing another of our mutual friends for a lack of diligence in his financial planning.

After years of late-nights and the resulting promotions in his field, our friend found a little nest egg in his bank account. Not enough to walk into a hedge fund manager’s office, but more than most millennials can hope to have in disposable income by 25.

And so the little shutterbug was browbeaten into downloading a robo advisor app like Wealthsimple as a way of putting that money to good use.

It seemed like good advice. The money wasn’t growing in his chequing account and, as the old adage goes, you have to make your money work for you.

Although this is anecdotal, I believe the underlying issue, that millennials are either unsophisticated or outright uncomfortable with financial planning, is endemic.

I was never taught how to ensure my own ‘financial freedom’, and in a job market which is becoming increasingly contractual–that is to say, without any expectation of a pension or long-term benefits–a great many young people today will have to ensure their own security after retirement.

So why not robo advisors? Simply put, they cost far more than advertised.

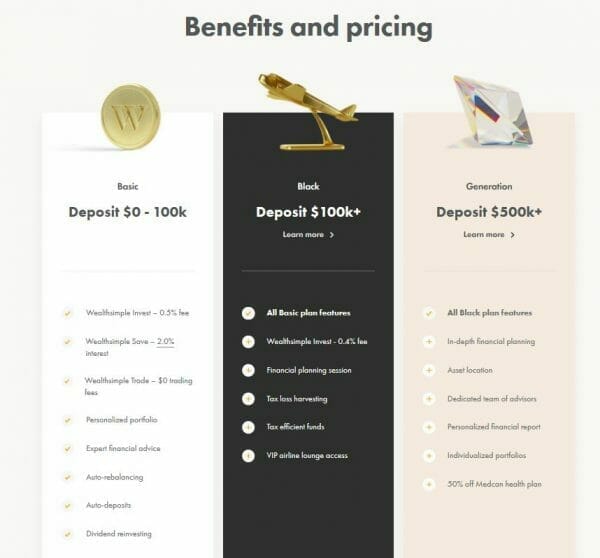

Take Wealthsimple, one of the largest robo advisors in the world. A basic account, meaning one with less than $100,000, will incur a 0.5% monthly fee on your investment.

Wealthsimple and its competition will compare their fees alongside those typically charged by the costs of hiring a human advisor to manage your money, usually ranging between 2.5-5% for low-figure investments.

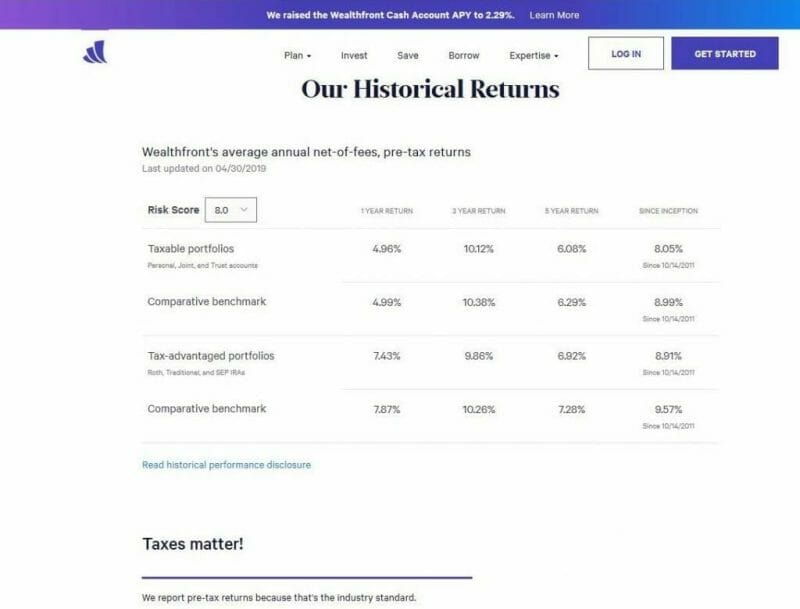

While that may not seem like much, it’s important to remember robo advisors almost never beat the market. Most years, they’re lucky to match it. See the image below for returns vs market benchmarks by Wealthfront, another robo advisor.

The reasons for this are the algorithms behind every robo advisor. Whereas a human advisor would, presumably, pick securities like stocks or options based on research or market knowledge, robo advisors are automated and rely on unsophisticated software to pick their securities.

First, users will be asked to fill out a questionnaire. This determines the level of risk said user is comfortable with. Higher risk means higher potential returns, but also, higher risk.

The advisor will then spit out a custom risk-rating for the user ranging from aggressive to conservative. This rating will influence the ratio of stocks (volatile but profitable) to bonds (low-risk, low-reward) your investment buys.

What’s wrong with this picture? Well, nothing. If you have $50,000 sitting in a chequing account and don’t have the time or energy to immerse yourself in the world of finance, a robo advisor would see you earn some returns on your money.

But if you want to maximize your investment, these are not the droids you’re looking for (for more riffs like this be sure to check out my financial-comedy podcast on SoundCloud).

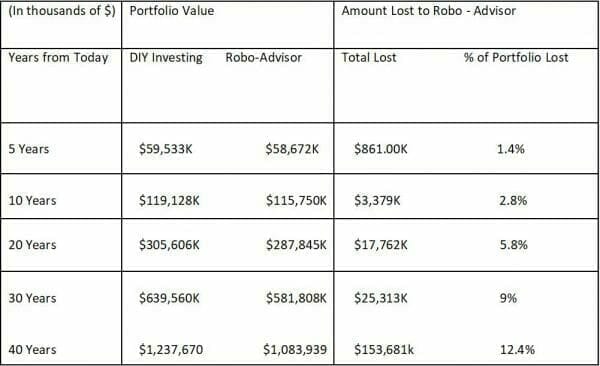

Here’s a little table we drew up to demonstrate just how much money these fees add up to over your lifetime.

Let’s use Ethan as an example – a 25 year old who’s decided to invest his savings with a robo advisor. Ethan has $15,000 saved and expects to invest an additional $7,000 each year going forward.

We’ll assume an investment annual growth rate of 6% a year (after inflation) which would be rather disappointing considering the SP500, a basket of the top 500 American public companies, is up 12,170.44% since 1950.

Our robo is not even coming close to matching the performance of the broader market, and it’s worth mentioning that truly exceptional funds measure their effectiveness by how often they beat the market.

Wealth Simple charges a fee of .5%, a rather heavy fee compared to competitors, but we will use it as our base metric due to its popularity.

Here’s what the picture would look like after 40 years – when Ethan is 65: The $153,000 Ethan loses is broken up into two central parts: the fees paid directly to the robo advisor, and the interest those fees would have made through compounding over the years.

There is another issue with the algorithm as well: robo advisors are not sophisticated enough to perform the complex financial maneuvers a human advisor can.

Sure, they advertise tax-loss harvesting, but Wealthfront, one of the largest robo advisory firms, was charged with false advertising by the Securities Exchange Commission in 2018 for failing to do so.

“From October 2012 through mid-May 2016, Wealthfront falsely stated in its TLH whitepaper that it monitored all client accounts to avoid any transactions that might trigger a wash sale…From October 2012 through mid-May 2016, at least 31 percent of accounts enrolled in Wealthfront’s TLH strategy experienced some wash sales.”

–The Securities Exchange Commission

It’s too complicated for our purposes, but a wash sale is something you want to avoid.

That said, human advisors have there issues as well. A recent study by the S&P Indices vs Active (SPIVA) found over 75% of Canadian money managers underperformed in 2018 against their benchmarks.

In plain English, investing in a market tracker, which promises to do no better and no worse than the market as a whole, and just forgetting about it would have made more money than three quarters of all Canadian advisors.

Our advice? Do it yourself. See how we break down company reports at Equity.Guru and replicate it in your own research. Nothing makes us happier than hearing our stories helped someone put a down-payment on a house.

Take the time to learn markets and talk with a financial advisor at your bank, but know what you’re going to ask when you get there. It’s slow going and much easier with a mentor, but there is no better way to secure your financial independence.

But, hey, life gets busy. We get it. I know people who work two or three different jobs and don’t have the energy to do much but plop down in front of the couch after a long shift.

We’re working more for less these days. The rise of contract work means fewer pensions, and some employers are even cutting existing pensions to stay afloat. My thoughts? All the more reason to take charge.

–Ethan Reyes

Leave a Reply