What happens when a global pandemic meets a price war on oil? Or, what happens

when severe practical problems meet ineffective policymakers? Rather, what

happens when an exogenous shock exposes a fragile system that fails to engage

critically in its own risk assessment? Oil prices go negative.

US oil futures expiring tomorrow entered negative territory and plunged below

zero for the first time on Monday. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) closed at

+$18.27/barrel on Friday and closed the day at -$37.63. It basically means that

traders are now willing to give you ~$38 for the right to hoard a

barrel of oil. Let’s examine the following: what happened, why it

happened, what it means, and what’s next for the current glut in oil.

What Happened?

Oil prices turned negative for the first time. More specifically, the prices of

oil for the futures contract expiring tomorrow went negative. The

prices of futures contracts expiring in the coming months still fell

but didn’t go negative.

Here’s how that happens – imagine the following:

You have dinner every day, but some days you like a milkshake for dessert, which

you order from the local deli. Now you’re the type that likes to plan everything

out, so you’ve already placed an order on UberEats for a Milkshake to arrive on

Monday.

Except it’s Monday and you had leftover cake from for dessert. But wait! You had

already placed an order, and now you can’t cancel it because the restaurant has

made it and sent the delivery guy on his way! So now you must find

another buyer for this milkshake in the time that the delivery man

arrives. You now try and sell the milkshake in the open market and see if anyone

wants it. No one does.

The milkshake usually goes for $10, so you try selling it for ten bucks, but no

one wants it. Prices begin to drop. “$8 dollars… $5 dollars? 50% off? Someone?

Anyone?” No one wants it. “$0 – free”. You give up, and say “Guys!! hey guys!!!

here’s a free milkshake, just give me your address and you’ll get it for free.”

“Nah. What weirdo has a milkshake for dessert anyway?” – people say.

Screw it. You really don’t want the milkshake. It’ll screw your diet.

You’re now willing to pay someone to take the milkshake off of your

hands. You want to get rid of it that badly. You’re willing to pay someone $5?

$10? $20? Still, no one wants it.

“Geez. How much do I have to pay someone to take my milkshake? $37?”

Finally. One person wants it.

That’s what happened in the markets today. Except it wasn’t really a

milkshake but a barrel of oil.

Traders were willing to pay other people for their ‘Futures’ contracts

expiring tomorrow so that they could take it off their hands and have to physically settle the contract, getting delivery.

“The order” is essentially the futures contract

that determines who has the right to take delivery.

You might say, “Cool! Can I open a trading account and get paid to own oil?” You

could. But I’d recommend against it. Primarily because even though you

get paid $38 per barrel, it means you’ll have to pay for shipping and handling

on your own.

If you can find some delivery company willing to ship you a single barrel of oil

at your doorstep for $X, and the $X is lesser than $38, by all means, go ahead.

Stockpile oil.

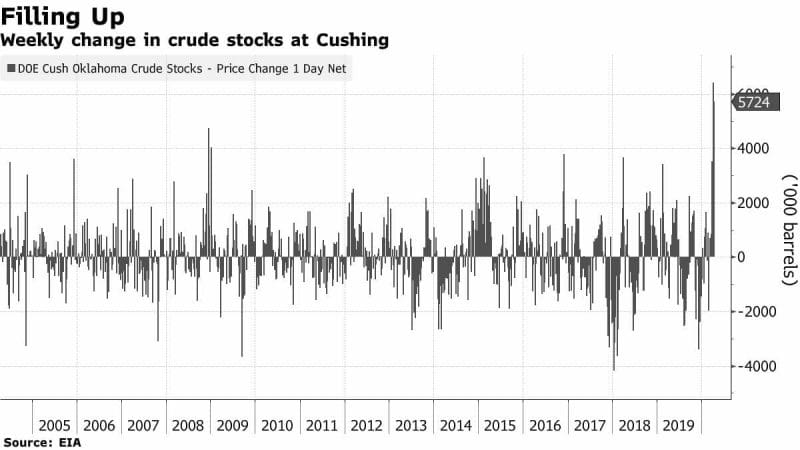

But at some point in time, your house will run out of space. A similar thing is

also happening to current large scale inventories of oil in the US. Especially

the one in Cushing, Oklahoma.

Why Did It Happen?

Reason 1: COVID-19

The COVID-19 Global Pandemic sent the world on a global lockdown, which in

effect killed the immediate and near term demand for travel. Moreover, the

social distancing policies in play killed any luxury consumer behavior that

would have otherwise happened – like travel.

As small businesses and firms struggled to survive, it meant layoffs and job

cuts that sent unemployment levels to levels not seen before in US history.

The result: oil markets got a negative demand shock, sending down oil prices.

Reason 2: Price War

The context of Saudi Arabia and Russia entering a pissing contest has to do with

two things: production cuts and the status of the US as a net exporter of oil

(which it became last year).

According to the US Energy Information Administration, the US produced 19% of the total oil in

the world in 2019, while Saudi Arabia produced 12% and Russia claimed 11% of the

market share.

Oil prices around this time (towards the end of 2019) were around ~$60/b and

were projected to be falling with an OPEC+ meeting supposed to happen.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 sent demand down.

Now Saudi Arabia was pissed because it was 1) losing market share to the US, and

2) had to “compromise” more by taking production cuts. Nearly all OPEC+

members in their rational minds would agree that global markets need production

cuts. The debate happens when it comes to who will take the cut because

every nation employs people and has entire economies dependent on oil

exports.

Taking on production cuts meant bearing the unit economic/breakeven costs for the respective country.

So, Saudi Arabia launched a price war with Russia and threatened to oversupply

markets. It did, and oil prices fell to levels not seen since the 1980’s.

Reason 3: The Way Oil Is Traded

Believe it or not, the way the physical commodity – oil – is traded in the

financial markets – futures – had a role to play in why prices went below zero.

A futures contract near the time of its “expiration” means that the trader has

one of the three following options:

- Offset the position – create a closing order & realize gains or losses

- Roll over the position – to a future date. You still own a contract, but it

just expires in the future - Take Physical Delivery – you bought a contract when it was, say $20/b,

congratulations, you got it. Now you send an address to get it delivered

Option 1: Offset the position

This is often the easiest (not talking about today) option employed by traders

where you close out the trade. You create an opposing order for the one you

created when you opened the trade, and realize all of the gains or losses you

made on the instrument. You do NOT have to take physical delivery. It’s somebody

else’s problem now.

If you went long – you create a sell order for the contract and then whoever

bought it has to specify an address and take on delivery.

If you went short – you create a closing buy order to cover your short. You now

own the contract which means you either a) set up a time and place for delivery,

or b) sell it again to someone else and have it be their problem (this

is also how you would close out a short position on a stock).

Option 2: Roll Over

When you do this, you essentially say “I still want the milkshake, but I don’t

want it this Monday, I want it the next one.” In this

instance, you move your position from your current, “front month” contract to

another contract due further out in the future.

Here, you have to simultaneously offset your current position AND establish a

new position in the contract due the next month. But who’s seen how many

milkshakes the world will want next Monday? Maybe there are not enough people

who want as many milkshakes in the future as they want to get rid

of their current milkshake orders today?

THIS was one of the catalyzing factors of today’s crash in oil, where traders

were unable to roll over their futures contracts, which no one is “underwriting”

or selling because everyone anticipates a negative demand shock and an

oversupply of oil. In essence, traders were forced, albeit for a brief

period of time, to find someone, anyone, to take delivery and have to pay for

it.

Option 3: Physical Delivery

If you were long and had bought the contract, it meant someone underwrote it or

had a “short position” on this trade, who now has to comply and settle the

contract, which is legally binding. So YOU better have a place to store it.

In this instance, you provide the time and place for delivery from whomever you

bought the contract from. If you were trading equities markets or indices

futures, the settlement is made in cash.

Reason 4: The USO ETF

This is a fun one. Days before the expiry of a futures contract are often

volatile, as it means that the bill is due and you’re getting closer to physical

markets from paper markets.

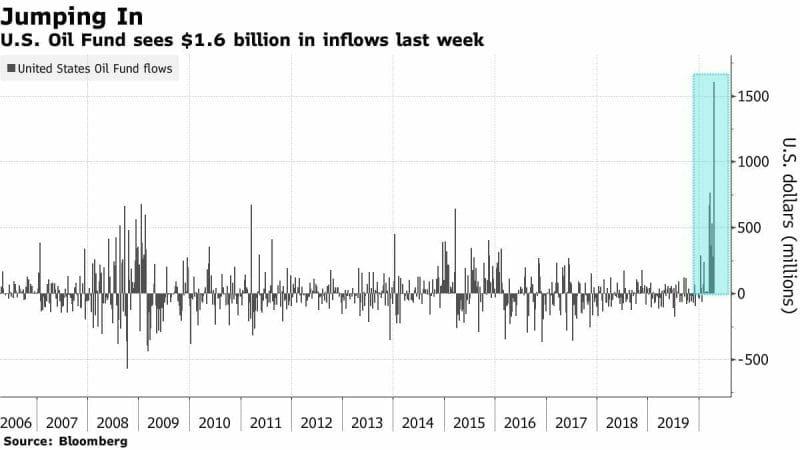

The largest crude oil ETF in the US ($USO) saw a record level of capital inflows

last week as investors thought the oil market had bottomed out. LOL. The May contract

for WTI had over 25% of all outstanding futures contracts held by the ETF.

Last week, the ETF rolled over its position into the June contract and got out

of the physical delivery due in May. So now many were left holding the bag to

get the delivery on the contract expiring tomorrow (set to deliver in May).

Reason 5: The Nerdy Stuff

Another cool concept that explains the dramatic plunge in oil comes from

economics – for oil has price inelastic demand AND supply.

The price elasticity of demand for a good is the degree to which the demand for

a good responds to a change in price. For luxury items, this is high, because

cheaper vacations and rental homes mean more vacations and rental

homes. For essential goods, this can be extremely low – like oil – where no

matter how cheap the product, you’re not suddenly going to buy more or less of

it just because it is cheap or expensive.

The price elasticity of supply for oil is also extremely inelastic. It’s not

like a toy factory where production costs are fixed, so even if no one wants to

buy your toys, and the price is zero, you can shut down production and incur the

cost of rent only. Or, if there is suddenly greater demand for toys, you can use

your factory to ramp up production.

For oil, this isn’t the case because once the hole has been drilled, the oil

will continue to ooze out of the earth, and you better find a place to store it.

Even if it means paying someone to do so.

You can’t produce more or less in the short term if the prices are suddenly very

high or very low.

What it means

One thing it certainly means is that there are more futures traders speculating in

the markets who don’t know what they are doing than there are who actually know

how to trade the instrument.

It means that traders, investors, and global markets were largely unprepared for

both the price war on oil and the ongoing global pandemic. With no airplanes

flying, no ships sailing, no one driving around, and no more large scale

manufacturing happening – no one is buying or is even willing to buy.

Near the time of expiration, prices of the futures contract are a closer

approximation of the physical price of oil. This makes sense because if it were

not the case, then traders could profit from the difference in trading the

futures contract and the physical price of the commodity, which would not make

sense.

The contract went negative because *this one* was set to have a delivery at the

inventory in Cushing, OK, but one wanted to pay for the delivery and storage.

They just wanted to get rid of the instruments that they no longer wanted.

Pretty badly.

We briefly experienced a market where there were many sellers but little to no

buyers.

What’s next

For Futures Markets

It means that producers and traders need to find inventories to hold oil because

they are stocking up. One of the largest US inventory is in Cushing, Okla, and

nearly every barrel of oil is rushing to get there. As of last month, this was

at 78% storage capacity.

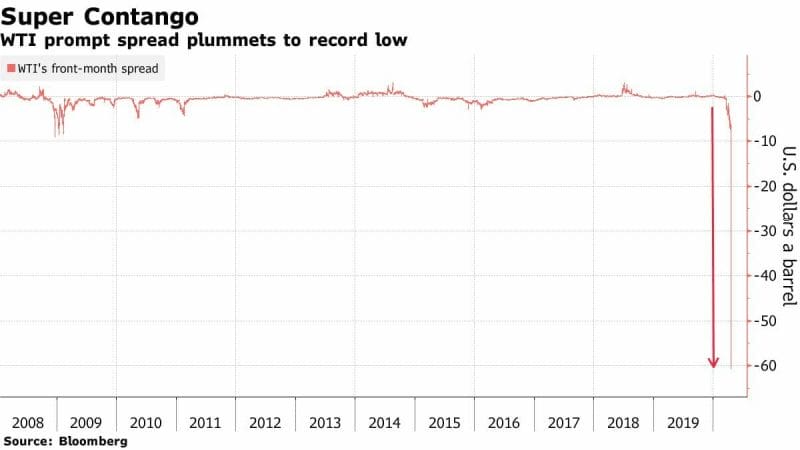

The high cost of “rolling over” means that there is a huge discount on the price

of oil to be available for delivery sooner rather than later.

So investors will lose more money each time they roll over their contracts. The

contracts expiring later cost more, so your losses run deeper.

For Oil Markets

The vast majority of US companies need oil to be above

$40/b to break-even. Oil production carries with itself major risk because

it is impossible to store during a glut and impossible to

abandon because of EPA regulations. You can’t just dump it in the ocean

(unless you’d like Greta to bang on your door).

Crude producers have already shut

down 13% of the American drilling fleet last week. While production cuts are

happening, they aren’t happening quickly enough to avoid storage facilities to

fill up to maximum levels.

Oil markets are complicated because there are different types of oil that are

available, and there are several sophisticated futures contracts that are traded

on them. The contract going negative was for WTI, but if such a macroeconomic

landscape continues, Brent and other types of oil could soon be following suit.

For the Fed and the Government

When you have one hammer, everything begins to look like a nail. The solution –

print money, cut rates. It means that if the current climate in oil markets

continues, we could soon be seeing a specific relief program for oil firms from

the government and firms filing for bankruptcies.

It means the government can allow these operators to fail and have their assets

stripped and then sold for parts by respective and legally entitled creditors.

But this would plummet their stock prices, and cause equities markets to fall.

Or. It could do what it always does – bail them out.

Whiting Petroleum was an oil producer in the US which in 2016 had a price of

$353/share with an $11 billion market cap. It filed for bankruptcy earlier this

month and currently trades at $0.37/share with a $31 million dollar market cap.

Despite having close to $600 million in cash, the board felt this was the

optimal decision.

Oil firms have high operating costs, so it means they must now either have the

spare cash in their bank accounts to survive or raise more debt to finance their

breakeven (or loss minimizing) cost. Because you can’t prevent the hole you

drilled from leaking oil.

Or, the US government bails you out and offloads the private risk that companies

took, and offloads it to the taxpaying citizen, making it a public loss. This

asymmetric distribution of risk and reward is precisely what capitalism

isn’t, but that’s a debate for another day.

For Canada

Once again, the way futures contracts are structured has come to rescue Canadian

firms. This is because the WTI contract that went negative is set for delivery

in May, while Canadian contracts are set for delivery in June. The prices for

the Canadian contracts fell but haven’t gone negative just yet.

The unique advantage of US oil is that its cleaner and, well, in the US.

Canadian oil is not as high grade and needs to be exported, so the cost of

delivery and export is higher. If the glut continues, Canada could end up

suffering much, much more.

The Conclusion

The truth is that the world is facing a complex situation it was neither

prepared for nor has witnessed in the past ever before. It comes without a

playbook, and the complexity of the global economy and financial markets make it

increasingly difficult to isolate and pinpoint unique chains of causation.

Should you not worry as much because negative prices were merely a result of

stupid day-traders and the way futures contracts are structured? Or should you

worry a lot because this is reflective of the degree to which global demand for

oil prices has fallen? Was it all of the reasons mentioned above or only some of

them? Did one matter more than the other?

I can’t draw your own conclusions for you, but I can tell you that we are

currently witnessing history. If oil markets are telling us a tale this

shocking, there’s clearly a few missing pages from the equities markets’

playbook.

Oil markets did recover after the historic carnage they witnessed on Monday, but

if this is a recovery or yet another market mispricing, who can tell?

Till then, it’s probably best to stick to trading what you know rather than

speculating on what you don’t.

Leave a Reply